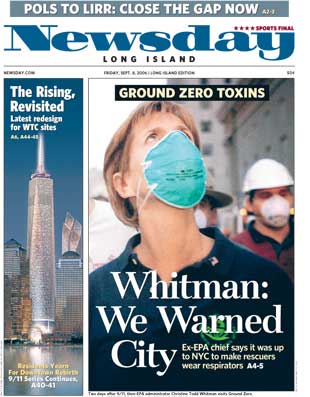

The blogosphere and mainstream media have been abuzz the past few days over ABC/ Disney's "Path To 9/11," the right-wing attempt to rewrite the history of that day. But the Bush administration's invitation to Fantasyland will actually begin one hour earlier tonight with the airing of a 60 Minutes Katie Couric interview of former EPA Administrator Christine Todd Whitman about the Bush administration's role in the disease that is now plaguing thousands of Ground Zero cleanup workers and residents.

The blogosphere and mainstream media have been abuzz the past few days over ABC/ Disney's "Path To 9/11," the right-wing attempt to rewrite the history of that day. But the Bush administration's invitation to Fantasyland will actually begin one hour earlier tonight with the airing of a 60 Minutes Katie Couric interview of former EPA Administrator Christine Todd Whitman about the Bush administration's role in the disease that is now plaguing thousands of Ground Zero cleanup workers and residents.For those of you just tuning in, the Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York released the largest study yet of thousands of Ground Zero workers confirms "that the impact of the rescue and recovery effort on their health has been more widespread and persistent than previously thought, and is likely to linger far into the future." In a nutshell, former recovery workers are getting sick and dying from the effects of inhaling smoke and dust containing a toxic burning brew of caustic concrete dust, asbestos, PCBs, jet fuel, and plastics, lead, chromium, mercury, vinyl chloride, benzene, human bodies and thousands of other toxic substances. The pulverized concrete alone has been characterized as so alkaline it is like inhaling lye.

The immediate problem was that recovery workers didn't wear respirators -- because OSHA didn't enforce the law, because Whitman's EPA had assured New Yorkers that the air was safe to breathe, and because the White House put more emphasis on politics than on public health, removing "alarming" language from EPA press releases and rushing the re-opening of Wall St.

Whitman claims that the EPA had warned the city of the toxic dust and blamed city officials for the ongoing disaster. "We never lied," she said.

Whitman claims first that the city had been warned about the toxic nature of the dust, and that EPA statements that the air was safe referred only to the ambient air around lower Manhattan, not Ground Zero itself.

"The readings (in lower Manhattan) were showing us that there was nothing that gave us any concern about long-term health implications," she tells Couric. "That was different from on the pile itself, at ground zero. There, we always said consistently, 'You've got to wear protective gear."Let's look at some of Whitman's quotes:

"There is no reason for concern," referring to asbestos measurements at Ground Zero and elsewhere in lower Manhattan.If she was only referring to Ground Zero, it's not hard to see why people didn't get it. A 2003 report of EPA's Inspector General found that although EPA press releases made some distinction between assuring the safety of the general public combined with more concern for the Ground Zero site itself, overall the communication was unclear and was one of the major factors contributing to the failure of many workers to wear respirators:

-- Christine Todd Whitman, September 15, 2001

"New York is safe."

-- Christine Todd Whitman, September 16, 2001

"We are very encouraged that the results from our monitoring of air quality and drinking water conditions in both New York and near the Pentagon show that the public in these areas is not being exposed to excessive levels of asbestos or other harmful substances. I am glad to reassure the people of New York and Washington, D.C. that their air is safe to breathe and their water is safe to drink."

- Christine Whitman, Sept. 18, 2001

A significant factor [why respirators were not worn]was the desire to save lives without regard for personal safety in the immediate aftermath of the disaster. Other reasons appeared to include the respirators’ interference with the ability of emergency workers to communicate, lack of training, lack of enforcement of safety measures at the site, and conflicting messages about the air quality at Ground ZeroMany of the air measurements taken by OSHA, for example, were within "acceptable limits," while for others there were no limits or no ability to measure. In addition, there was no ability to determine the synergistic effects of chemicals -- the health effects of exposure to multiple chemicals at the same time instead of each one individually:

Thus, on one hand workers had information suggesting that the air quality was not bad, but a message to wear respirators on the other. This report also noted the poor example set by political figures, celebrities, and even supervisors who visited the site but did not wear respirators.In addition, the IG interviewed numerous consultants and contracting firms were were under the impression that EPA assurances applied to Ground Zero, as well as the general population.

One of the most upsetting findings of the IG was its conclusion that White House officials had instructed the agency to be less alarming and more reassuring to the public in the first few days after the attack than EPA officials originally wanted to be. In fact, the White House Council on Environmental Quality ordered EPA to add reassuring information and delete cautionary information from at least one press release.

The title for the original version of one news release was, "E.P.A. Initiating Emergency Response Activities, Testing Terrorized Sites For Environmental Hazards." In the final version, the second clause was changed to read, "Reassures Public About Environmental Hazards." In the same release, a section that said, "Even at low levels, E.P.A considers asbestos hazardous in this situation" was deleted and replaced with a section that read, in part, "Short-term, low-level exposure of the type that might have been produced by the collapse of the World Trade Center buildings is unlikely to cause significant health effects."Ultimately, according to the IG, the content of EPA's press releases were based more on politics than on science.

The draft of the inspector general's report also says the agency "did not have sufficient data and analyses" to make a "blanket statement" when it announced seven days after the attack that the air around ground zero was safe to breathe. "Competing considerations, such as national security concerns and the desire to reopen Wall Street, also played a role in E.P.A.'s air quality statements," the report said.The IG also found that

a federal emergency response team prepared a report on the day of the attacks recommending that respirators be used at ground zero.And earlier this year, Judge Deborah A. Batts of Federal District Court found that Whitman had deliberately mislead the public when she reassured the people of New York after the collapse of the World Trade Centers that the air was safe to breathe in lower Manhattan and Brooklyn. The result of Whitman's lack of concern was devastating for recovery workers, according to Dave Newman of the New York Committee on Occupational Safety and Health who argues that after Whitman's statement, employers "had a green light to say, 'We don't need to use respirators because the E.P.A. says the air is OK.' "

But the report was never issued because it was decided that New York City, and not the federal government, should handle worker protection issues.

Whitman testified last week about the EPA's response and received a hostile reaction from New York's Congressional delegation as well as from Joseph Zadroga, the father of NYPD Detective James Zadroga, who died at age 34 next to his 4-year-old daughter in January after fruitlessly seeking treatment for months for his failing health. Zadroga had worked over 500 hours on the pile and he was the only Ground Zero worker officially linked to work at Ground Zero. Referring to Whitman's testimony, the elder Zadroga said "I think she should go to jail."

In addition to denying that EPA's assessments of the hazards at Ground Zero mislead the public and the workers, Whitman blames the city of New York for the fact that few workers wore respirators. The problem, according to Whitman, was that the EPA didn't have the authority to force workers to wear respirators. The city of New York was in charge and they bear the responsibility.

"We did everything we could to protect people from that environment and we did it in the best way that we could, which was to communicate with those people who had the responsibility for enforcing," says Whitman. "We didn't have the authority to do that enforcement, but we communicated (the need to wear respirators) to the people who did," she tells Couric. "(In) no uncertain terms (city officials were warned of the danger). EPA was very firm in what it communicated and it did communicate up and down the line."Whitman is partially correct in that the City of New York, and specifically Mayor Rudi Giuliani, bear their share of responsibility for putting politics over public health. In a letter to New York officials dated October 5, 2001, the EPA expressed concern over the air at Ground Zero:

"Who had ultimate authority over the site?" asks Couric.

"Really, the city was the primary responder," replies Whitman.

"In addition to standard construction/demolition site safety concerns, this site also poses threats to workers related to potential exposure to hazardous substances," including building materials, hazardous materials stored in the buildings and combustion products emitted from the smoldering rubble, the letter states.The next day

a top city Health Department official wrote a three-page memo raising "critical environmental issues" related to the disaster.And on September 29, 2001, Mayor Giuliani assured New Yorkers that "Although they occasionally will have an isolated reading with an unacceptable level of asbestos … it's very occasional and very isolated. The air quality is safe and acceptable."

Associate Commissioner Kelly McKinney wrote that there were deep disagreements between the city's Office of Emergency Management and the Department of Environmental Protection over whether the air was safe enough to allow people back into the zone.

"The mayor's office is under pressure from building owners and business owners in the red zone to open more of the city to occupancy," McKinney wrote. "According to OEM, some city blocks north and south of Ground Zero are suitable for reoccupancy. DEP believes the air quality is not yet suitable for reoccupancy. I was told the mayor's office was directing OEM to open the target areas next week." McKinney, now with OEM, did not respond to a written request for comment.

Dropping The Ball On Respirators

But in the interview, Whitman seems to suggest that it was actually the workers themselves who were to blame for not paying attention:

Whitman understands that among first responders at ground zero, some may have been confused over that message.Ultimately, of course, the US Congress gave neither EPA nor the City of New York the responsiblity for worker safety. The agency tasked by Congress to ensure the health and safety of American workers is the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 made no exceptions for federally declared disasters.

"It's hard to know … when people hear what they want to hear and there's so much going on, that maybe they didn't make the distinction," says Whitman. But city officials were clearly made aware of the danger on the pile, she says.

But OSHA didn't see it that way:

As the magnitude of the recovery operation grew clearer, attempts were made to bring order to the operation. On Sept. 20 the city issued its first safety plan, and it asked the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to take charge of distributing respirators. In what would become a controversial move, OSHA used its discretionary powers to decide not to enforce workplace safety regulations but to act in a supportive role that would not slow down operations.According to OSHA's official report of the agency's response, Inside the Green Line:

Early on, Assistant Secretary [of Labor for OSHA, John] Henshaw determined that the best role for the agency at the WTC was to provide guidance and assistance with a sound safety and health plan.Now, reasonable people can argue about the precautions that rescue workers can be expected to take in the immediate aftermath of a mass disaster where lives are at stake and very hand is needed. In the case of the World Trade Center attack, that period of time lasted for perhaps a few days. After that, the rescue became a recovery that went on for nine months -- without any OSHA enforcement.

"When we worked out that plan with the site command staff, we agreed that the rescue effort must not be hampered," explained [OSHA Region II Administrator Patricia] Clark. "Given that the site was operating under emergency conditions, it was normal that we should suspend our enforcement action and assume the roles of consultation and technical assistance." Enforcement takes time and can affect the speed of abatement. OSHA's goal from the start was protection, not citation.

And similar "emergency conditions" didn't stop the Pentagon from escorting workers off the site if they weren't wearing proper respiratory gear and more than 90 percent of the workers at the Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island, which was overseen by the Army Corps of Engineers, wore respirators, according to the Times.

The result, was of course, disastrous. As the Sierra Club points out in a recent report,

New York City lost at least twice as many firefighters from active duty after 9/11 because of respiratory health impairments from 9/11 dust exposure as it lost on the day of the attackThe Fire Department of New York lost 341 firefighters and two paramedics on September 11, 2001. As of May 2004, 325 firefighters affected by Ground Zero reportedly still were on restricted light duty, 69 were on medical leave, and 320 with lung impairments had retired.

Unfortunately, this "advisory" role for OSHA has now been permanently incorporated into Homeland Security's National Response Plan as the Sierra Club report explains:

Yet, despite the illnesses that arose among Ground Zero workers, both OSHA and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) have incorporated lack of enforcement into new federal plans for emergency response. And in national emergencies, OSHA does not have the final word on safety. Apparently our first responders are brave but expendable.And, in fact, the same mistakes were made following Hurricane Katrina. OSHA did not resume regular enforcement in the area south of Interstate 10 in Mississippi until June 28, 2006. The agency has still not resumed regular enforcement in the hurricane ravaged areas of Louisiana.

OSHA's report on the World Trade Center disaster boasted that there were only 57 serious injuries during the 3.7 million hours of work on cleaning up the pile at Ground Zero, significantly lower than similar projects, and credits the "WTC partnership" for this work. The final sentence, in bold in the original, is particularly chilling after the release of last week's Mt. Sinai report:

After September 11, 2001, not one life was lost inside the green line during the recovery effort.Would that that was still true today.

Related Stories

- 9/11: Giuliani's Dumb and Deadly Decisions, September 8, 2006

- 9/11 Anniversary: Don't Forget The Workers, September 6, 2006

- Ground Zero Workers: The Continuing Cost Of A Cover-Up, August 28, 2006

- Ground Zero Workers: Neglected Victims of "The Largest Acute Environmental Disaster That Ever Has Befallen New York City", July 31, 2006

- World Trade Center Tragedies Continue, May 15, 2006

- Confirmed: NY Detective's Death Caused By World Trade Center Dust, April 13, 2006

- EPA's Whitman: Guilty of Deceiving The Public on Post-9/11 Safety -- Or Not?, February 4, 2006

- Just letting people die like dogs" 9/11 Dust Fatalities Continue to Climb, February 26, 2005

- Coughing Up Gravel: Another Victim Of 9/11, July 13, 2005

- World Trade Center Workers: Still Suffering Three Years Later, September 14, 2004

- NYCOSH Awards Speeches:The World Trade Center Worker and Volunteer Medical Screening Program at Mt. Sinai -- Drs Steve Levin and Robin Herbert, June 9, 2004