The Chicago Tribune's second installment of "Throwaway Workers" appears today. It deals with immigrant workers who have been seriously injured on the job, and the lack of medical or financial support they receive -- because the companies haven't provided insurance, because they just go out of business, or because they just refuse.

The Chicago Tribune's second installment of "Throwaway Workers" appears today. It deals with immigrant workers who have been seriously injured on the job, and the lack of medical or financial support they receive -- because the companies haven't provided insurance, because they just go out of business, or because they just refuse.It's depressing reading, even for someone like me who's up to his elbows in these stories every day. Reading their series is like re-reading The Jungle or some other century old story of how badly workers were treated before we realized that it was inhumane to treat humans like that, and passed laws to criminalize such treatment. The problem, of course, is that these stories are taken from toay's workplaces, and for that we should all be ashamed.

But before going into the gory details, I want to take a moment to sing the praises of the authors, Steve Franklin and Darnell Little. Most reporters don't even take the time to notice the conditions under which workers work, particularly those who are at the bottom of the heap. Even where journalists report on working conditions, injuries and deaths, they rarely go beyond "the employer said this..." and "OSHA said that..."

Compare that with the work they've done on this series:

Work on these articles began in December when photographer Abel Uribe began interviewing injured workers and their families. Besides available government records and interviews, the stories are based on Tribune reporter Darnell Little's analyses of 35 years of U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration records, 14 years of Bureau of Labor Statistics worker fatality data and 12 years of national fatality records. Little and reporter Stephen Franklin interviewed workers and numerous government, public health and union officials, as well as worker safety advocates.As I said yesterday, while most of the Labor Day news articles deal with unions, statistics and politics, Franklin and Little are talking about real workers -- what Labor Day is really about. And the picture isn't pretty:

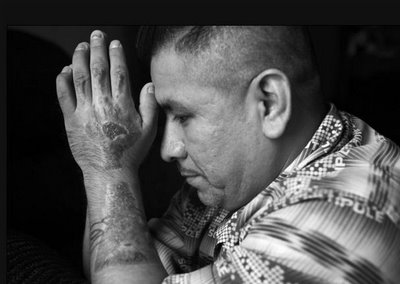

Raul Rosas lies in pain in a dark, foul-smelling hovel that resembles a shallow cave more than a basement.And the current media and election year political frenzy around "illegal immigrants" is making the problem worse.

Paralyzed in a workplace accident five years ago, he survives by selling fruits and vegetables from a wheelchair on a Chicago street corner. But now he is sick with a stomach infection and can't buy medication because he has no way to get to a drugstore.

Since losing the ability to walk, Rosas' life has shrunk to the barest existence. He is a veritable ghost, and a depleted one because he is an illegal immigrant and therefore ineligible for all government assistance beyond emergency room care.

"It is very hard," he said dejectedly, turning his crumpled body away.

When an undocumented worker has an accident or gets sick, it puts pressure on the families, who must do without a paycheck, and it puts pressure on the public health system, because the workers are less likely to have insurance.

This is an issue at the heart of the debate over immigration reform: whether the economic contributions of illegal workers outweigh the costs, and whether they should remain in the U.S. at all.

What's been overlooked are the risks the workers take, the price they pay and the impact.

Because they tend to exist in the shadows, beyond the workplace protections that others take for granted, the undocumented are more likely to face hardships after their accidents. Some return home. Others remain in the United States, partly because they still can earn more income here.

Rosas, an immigrant from Mexico, was hired to remove a tree from a back yard. The tree fell and seriously injured him.

"The guy he was working for didn't even want to call the ambulance," said Ramon Canellada, a disability coordinator at Schwab Rehabilitation Hospital on Chicago's South Side, where Rosas was briefly treated.

Since then, Rosas has not received any government-supported therapy, or any medicine or a wheelchair. He bought those himself. One of his few protectors is Canellada, who has tried to keep an eye on him, even scrounging for parts for Rosas' electric wheelchair.

Fiercely independent, Rosas, 48, lives on whatever he earns from fruit-and- vegetable sales during warm-weather days. He pays $300 a month for his tiny corner of the basement, which he shares with two other Latino workers.

Before the recent uproar over illegal immigrants, Rene Lune, a worker with Access Living, a Chicago agency that helps the disabled, would refer injured Latino workers such as Rosas to public health agencies, which might overlook their immigration status and provide help.OSHA, to its credit, recognizes that there health and safety conditions for immigrant workers is a problem. But, although the agency is attempting to hire more Spanish speaking inspectors and building coalitions with community groups in some cities, their efforts had little effect for a variety of reasons -- the inadequate resources the administration has dedicated to the effort, inadequate OSHA fines, along with the eternal tension between jobs and safety:

"Now with all of the strict background checks, [agencies] won't do it," Lune said.

The worker's compensation system is supposed to help injured workers such as Rosas with recovery--and that includes illegal immigrants. Nearly every employer in Illinois is required to provide such coverage.

But because of the risky or marginal jobs held by illegal workers and the types of employers they work for, the system hasn't exactly benefited Latino workers.

Many are injured while working for small businesses that have neither health insurance nor worker's compensation coverage, said attorney Jose Rivero. Some larger companies, he added, don't think they have to provide benefits for their "clandestine" workforce.

For years the state did little to make sure employers complied with the state's worker's compensation law. From 1983 to 1996, the Illinois Workers Compensation Commission kept shut its compliance unit for budgetary reasons, according to state officials. It now has four workers, none of whom speaks Spanish.

Asked how many employers comply with the law, state officials, replying by e-mail, said they didn't know but were looking for ways to find that out.

To begin, the agency's ranks are limited, they say. Then there is the wave of fear that swept Latino communities last year after Homeland Security officials, posing as OSHA representatives, called a "mandatory" safety workshop in North Carolina and arrested the workers who showed up. OSHA officials say that was a wrong thing to do and won't happen again.Finally, take a look at the comments back on the main page of the series (right hand side, in red). There are a troubling number that are of the opinion that because they're "illegal," they deserve what they get.

There also is the broad reluctance of workers and others to identify dangerous workplaces.

"It is better. People know who we are," said Michael Connors, OSHA's regional head in Chicago. "But it is not like we are getting any calls or complaints from the community."

Nor, Connors said, do physicians alert his agency.

Jose Oliva of the Chicago-based Interfaith Committee on Worker Issues, an advocacy group, said it has a unique arrangement with OSHA that allows it to relay workers' anonymous complaints. It was the first of its kind in the nation, and OSHA officials hailed it as a way to reach workers.

But sometimes Oliva is reluctant to name companies.

"It is hard for us," he said. "You know you are putting people back into danger. [But] if the company went out of business, you would have 300 people out of jobs."

Not long ago he decided not to file a complaint with OSHA against a Bellwood company after it agreed to hire back about 25 Latinos who had been let go because they took time off to march in an immigration rally. Some workers had complained that the firm did not provide safety equipment and that fans failed to ventilate toxic fumes, Oliva said.

A month after the company rehired the workers, an explosion there killed a truck driver making a delivery and injured three factory workers and two firefighters. OSHA officials said they are investigating the incident at Universal Farm Clamp Co.

It's time to crack down on employers who hire illegal immigrants. As for the immigrants, they have a choice: take your chances working a dangerous job or leave the country.I've written about this before (here). We can deal with this issue on a practical basis: Not enforcing the law for immigrants just makes it more attractive for employers to hire them and makes work even more dangerous for everyone else (complain about you're working conditions and we'll just fire you and hire someone who won't complain.)

Submitted by: danielle

We can also look at the situation from a moral basis -- how we like to think of ourselves as a nation. My opinion is that the compassion of a nation should be measured by how they treat those who are most vulnerable. By that test, we're failing.