The first article is a story of a young man, Patrick Walters, killed in an uprotected 10-foot deep trench, only a couple of weeks after OSHA had cited the same company for sending workers into unprotected 15-foot deep trench. It's the story of OSHA refusing to issue a willful citation despite proof that the hazards were well known to the company, and finally the story of a federal workplace safety agency that wouldn't even refer this case to the Justice Department for possible criminal investigation.

Montgomery County Coroner's Office

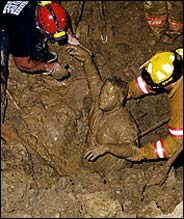

The body of Patrick Walters as it was removed from the trench that collapsed and killed him in 2002. His family's lawyers provided the photograph.

Where Barstow's McWane series may have left the impression that McWane was a uniquely bad actor, the devastation caused by the death of Patrick Walters in a collapsed trench is clearly only one of many similar preventable tragedies -- in unprotected trenches and elsewhere -- that are all too common in this country, yet are hardly reported or noticed by anyone except the families or co-workers of the dead.

Those involved in occupational safety and health, and all of you readers of Confined Space -- "The Weekly Toll," the article below and other items like the recent letter from the sister-in-law of an Ohio trench collapse victim (and other stories here, here, here and here)-- may be some of the few who have any idea of the devastation experienced many times every day in small towns and large cities across this country.

Barstow's second article -- "the first systematic accounting of how this nation confronts employers who kill workers by deliberately violating workplace safety laws" -- is, if possible, even more disturbing

every one of their deaths was a potential crime. Workers decapitated on assembly lines, shredded in machinery, burned beyond recognition, electrocuted, buried alive -- all of them killed, investigators concluded, because their employers willfully violated workplace safety laws.The reality is that the only employers who face substantial penalties are those who kill an employee or those very few who are unlucky enough to be the subject of an OSHA inspection. For a constantly moving and changing construction site, it is even more unlikely for OSHA to be on the scene at the same time that workers are being exposed to life-threatening conditions.

These deaths represent the very worst in the American workplace, acts of intentional wrongdoing or plain indifference that kill about 100 workers each year. They were not accidents. They happened because a boss removed a safety device to speed up production, or because a company ignored explicit safety warnings, or because a worker was denied proper protective gear.

And for years, in news releases and Congressional testimony, senior officials at the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration have described these cases as intolerable outrages, "horror stories" that demanded the agency's strongest response. They have repeatedly pledged to press wherever possible for criminal charges against those responsible.

These promises have not been kept.

Even when caught -- even having killed a worker -- even having killed a worker in full knowledge that the employee was working in an unsafe workplace -- the chances of paying a substantial penalty or serving jailtime are extremely remote. The employer of an Iowa worker killed in a confined space last July was fined a whopping $1,125. Even companies that willfully violated the law and killed workers

face lighter sanctions than those who deliberately break environmental or financial laws.The reasons: Lack of encouragement from Washington for criminal prosecutions, intimidation by industry lawyers, resistance by OSHA's lawyers, (the DOL Solicitors Office), the time it takes to put a case together when easier cases will chalk up higher numbers, and the fact that willfully killing a worker on the job is only a misdemeanor with a maximum jail sentence of 6 months, making prosecutors less likely to want to invest the time to go after them.

For those 2,197 deaths, employers faced $106 million in civil OSHA fines and jail sentences totaling less than 30 years, The Times found. Twenty of those years were from one case, a chicken-plant fire in North Carolina that killed 25 workers in 1991.

By contrast, one company, WorldCom, recently paid $750 million in civil fines for misleading investors. The Environmental Protection Agency, in 2001 alone, obtained prison sentences totaling 256 years.

But it doesn't have to be this way. If things are to change, the outrage generated by the death of Patrick Walters and the thousands like him must be translated by families, friends, co-workers, labor unions (and NY Times readers) into pressure on our politicians to create a system where employers who are trying to save a few bucks would no more consider putting a worker into a life threatening situation than your average citizen would consider robbing a bank because they are short of money. Until that happens, until there is a real fear of certain jail time, these tragedies will continue to constitute a daily toll.

But even under the best circumstances, few employers will ever go to jail -- and then only if someone dies. For those "lucky" enough not to kill someone -- yet -- or lucky enough to avoid an inspection by OSHA, there must be a better way to prevent such incidents. Ultimately, workers themselves must refuse to be fodder for employers trying to save a little time or a few bucks.

But that's not easy in today's conditions.

Barstow reports that

it was dangerous work, and [Walters] had known it. He told his mother of being buried to his waist in one trench. He told his father of being lowered into trenches on the bucket of a backhoe, leaving him no ladder to escape a collapse. "I just ask God never to let me die that way," he said to his wife.Giving workers the unchallenged right to refuse to work in hazardous situations without fear of reprisal requires better laws protecting a worker's right to refuse, meaningful enforcement of those laws and high penalties for violating them. Finally, it also means that workers need a real right to organize because ultimately, only workers protected by a strong union will feel secure enough to tell that boss, "Hey, I just came to work here. I didn't come to die."

His family urged him to put up a fuss. But he pointed out that he was only an apprentice, easily replaced. If he was seen as a troublemaker, he worried, his bosses would find an excuse to get rid of him. Their attitude, he told his father, was "either do it or go home."

And in truth, he did not have many better alternatives.

There has been some activity in Congress -- in the form of a billintroduced by Senator Jon Corzine -- to increase the maximum jail sentence from 6 months to 10 years. The response from the Chamber of Commerce: "Obviously we're not going to support the expansion of criminal penalties," said Randel K. Johnson, vice president for labor issues at the United States Chamber of Commerce.

Obviously.

And the response from OSHA Director John Henshaw:

Mr. Henshaw made it clear that he saw no need to change either the law or OSHA's handling of these worst cases of death on the job.We are entering an election year: President, all 435 members of Congress and 16 Senators. We have before us an opportunity that comes around only every four years to make sure that no candidate goes a week without having to respond to this question: "Suppose OSHA can prove that an employer knew a workplace is unsafe, but sends a worker to work under those conditions anyway and the worker is killed. Should that employer go to jail?" Or "Do you think that $5,000 or $50,000 or $150,000 is enough for an employer to pay who knowingly sends a worker into an unsafe workplace and the worker is killed?"

"You have to remember," he said, "that our job is not to rack up the individual statistics that some people like to see. Our job is to correct the workplace."

Or make up your own questions. These articles are being reprinted in papers all over the country. The proverbial iron is hot. Strike it now. Make workplace killing an issue that no one can defend.