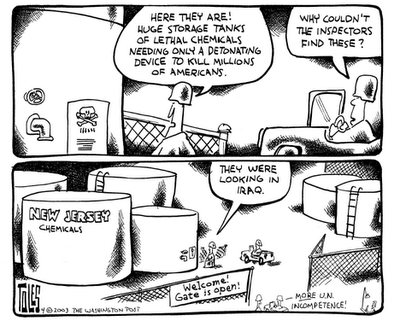

After five long years with millions of Americans living in the shadow of real chemical weapons of mass destruction, the US Congress seems poised to finally pass chemical plant security legislation.

After five long years with millions of Americans living in the shadow of real chemical weapons of mass destruction, the US Congress seems poised to finally pass chemical plant security legislation.But unless you're a chemical industry executive, it couldn't be worse.

The New York Times issued a blistering editorial today, blasting Republicans and the chemical industry for proposed chemical plant security bill that undermines homeland security:

Congress still has done nothing to protect Americans from a terrorist attack on chemical plants. Republican leaders want to give the impression that that has changed. But voters should not fall for the spin. If the leadership goes through with the strategy it seems to have adopted last week to secure these highly vulnerable targets, national security will be the loser.Well, the Republican leadership did go through with the strategy in the Conference committee today, hoping to have something to show off on the campaign trail. Congressional Republicans caved in to the chemical industry behind closed doors, attaching industry's language to a rider in the Homeland Security appropriations bill. The result is that we're all the losers -- especially those of us who live near chemical plants, refineries or wastewater treatment plants.

But, of course, not everyone was unhappy with today's vote:

The U.S. chemical industry embraced the Republican measure as a "fair compromise that will give DHS strong authority to secure America's chemical facilities," according to Jack Gerard, head of the American Chemical Council, who said his industry has already spent $3 billion enhancing security.Background

Dow Chemical, the largest U.S. chemical maker, also praised the bill.

There are 3,400 high-priority chemical facilities in this country where a worst-case release of toxic chemicals could sicken or kill more than 1,000 people, and 272 sites that could affect more than 50,000 people. Yet despite reports from government agencies and independent journalists since 9/11 that chemical plant security is seriously flawed, the Bush administration has refused to address the issue.

Shortly after 9/11, New Jersey Senator Jon Corzine introduced legislation that would have forced the chemical industry to implement, where possible, inherently safer technologies (e.g. substituting safer chemicals, storing smaller amounts of hazardous chemicals, etc.), along with increased traditional security measures.

The bill was passed unanimously by the committee. But then the American Chemistry Council (formerly the Chemical Manufacturers Association) woke up and along with their clients in Congress kill Corzine's bill, suggesting instead an legislation that focusee almost entirely on traditional security (guns, guards and gates), and relies on compliance with voluntary guidelines -- developed by the American Chemistry Council.

And that's were things stayed (and stayed and stayed) until last December when the state of New Jersey decided not to wait around for the feds to act and passed its own Chemical Plant security bill that required all chemical plants to take measures to reduce their vulnerability to catastrophes resulting from terrorist attacks and required 43 (of the state's 140 plants) using the most hazardous chemicals are required to review the potential for adopting inherently safer technologies.

Suddenly the chemical industry -- facing the prospect of being forced to comply with multiple different state regulations -- saw the light, seeing the immediate need for a (weak) federal law (that would pre-empt state laws). A couple of months later, right on schedule, after years of not paying much attention to the issue, the Bush administration finally decided to weigh in with a statement from Homeland Security chief Michael Chertoff announcing that he would propose turning chemical plant security over the to chemical industry.

Chertoff's plan would prohibit states (like New Jersey) from issuing their own plans, fearing that they would expose businesses to "ruinous liability" and would create "a regulatory regime that is doomed to failure." And any requirements for inherently safer technologies would present an "interference with business."

Senator Susan Collins (R-ME) and Joe Lieberman (D-CT) had introduced a bipartisan bill that did not pre-empt states like New Jersey from passing their own laws, but also did not require inherently safery technologies, although it did leave it to the the discretion of Homeland Security to decide whether there is any role for specific technologies. Because of the lack of pre-emption and the slight possiblity that Homeland Security might consider inherently safer technologies, the Collins-Lieberman bill was deemed unacceptable to the chemical industry -- and therefore to the Bush Administration and the Republican leaderhip in Congress as well.

What Happened Today?

Which brings us to today. Unable to pass a separate chemical security bill, the Republicans are up to their old tricks -- writing the chemical industry's bill in the conference committee as part of the Homeland Security appropriations bill.

As the today's Times editorial says:

It is outrageous that something as important as chemical plant security is being decided in a backroom deal. It is regrettable that Susan Collins, Republican of Maine, the chairwoman of the committee that produced the Senate bill, does not carry enough influence with her own party's leadership to get a strong chemical plant security bill passed. The deal itself, the likely details of which have emerged in recent days, is a near-complete cave-in to industry, and yet more proof that when it comes to a choice between homeland security and the desires of corporate America, the Republican leadership always goes with big business.The bill

- Exempts thousands of chemical plants from any regulations unless the DHS considers them high risk.

- Specifically exempts approximately 3,000 drinking water and waste water facilities.

- Keeps DHS from requiring safer technologies or any other "particular security measure" that could enhance security and eliminate the consequence of an attack.

- Fails to preserve state and local government's authority to set stronger security standards than the federal government as New Jersey now does.

- Gives the DHS no criteria for choosing high-risk plants. DHS has complete discretion to ignore plants where thousands of people are at risk while relying on dubious intelligence to select so-called “high risk” facilities.

- Fails to require chemical plants to ever submit security plans by any date certain to the DHS for approval.

- Sets no deadlines by which DHS must approve or disapprove plant security plans.

- Fails to require “red team” security exercises or involve plant workers in the development of security plans. All of the above are contained in H.R. 5695 adopted by the House Homeland Security Committee on July 28th.

- Contains “shutdown” authority that is more about public relations than enforcement. If the shutdown authority were ever used it would more likely be for a day or so and masks the light civil penalties for violators contained in their bill, (only $25,000).

“The most well known example of proven solutions that were rejected by the Conferees is the 2001 conversion of the Washington, D.C. sewage treatment plant. Eight weeks after the 9/11 attacks that plant ceased its use of chlorine gas and no longer poses a threat to millions of DC area residents.One of the major problems with the bill is lack of any requirement for high risk plants to consider inherently safer technologies. One of the main advantages to inherently safer technologies is that they not only protect against a terrorist attack, but also against the every-day run-of-the-mill domestic chemical accident. But even if the only threat we had to worry about was terrorism, how much sense does it make to only commit resources to guard a target (with questionable effectiveness) when in most cases it’s entirely possible to shrink or even remove the target completely?

EPA data show that 225 plants have taken similar actions since 9/11. However, nearly 100 water treatment plants each put 100,000 or more people at risk.This bill exempts all (approximately 3,000) U.S. water treatment plants from new security measures.

As outlaw Willie Sutton explained, they robbed banks because that’s where the money was. Terrorists would be tempted to attack chemical plants because that’s where the greatest potential for terror is. Take the money out of the banks -- or the catastrophic potential out of chemical plants -- and no one cares.

Chertoff and the Bush clearly don't get it (or don't want to get it):

Clearly a lot of chemical companies on their own, in meeting performance standards, will want to look at inherently safer technology as a means to reduce the risk, and therefore achieve what they need to achieve. But we have to be careful not to move from what is a security-based focus, as part of the type of regulation I'm describing, into one that tries to broaden into achieving environmental ends that are unrelated to security. There is an Environmental Protection Administration. They deal with environmental matters that are distinct from security. And I want to make sure that we don't allow our focus on security to become a surrogate for achieving ends that may very well be worthwhile but ought to be pursued in a debate in another forum. (emphasis added)As the New York Times said last summer when an inherently safer technology amendment was being voted on:

The industry is fighting for its right to use whatever chemicals it deems best, or most profitable, no matter how much risk that poses to people who live, work and attend school nearbyWhat Can Be Done Now

Right now, we're the bottom of the ninth in the great Chemical Plant Security Debate, the score today stands: Chemical Industry - 1, National Security - 0. But the game isn't over yet

The entire Homeland Security appropriations bill must still be voted on by both Houses of Congress. House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi is reportedly planning to force a House vote on the chemical security rider later this week and hopefully there will also be a separate vote in the Senate.

So get your dialing and faxing and e-mailing finger ready. There will be some lobbying to do.

Details to follow Related Articles

(Everything you ever wanted to know about the last four years of the chemical plant security debate)

- House Set To Do Harm To Chemical Plant Security, July 27, 2006

- Chemical Plant Security: The Plot Sickens, April 17, 2006

- Homeland Security To Turn Chemical Plant Security Over To Industry, March 23, 2006

- Ho, Hum. Yet More Chem Plant Security Stuff, January 23, 2006

- NY Times Says It's Time To Take Chem Plant Security Seriously, May 22, 2005

- Itty Bitty Steps Forward On Chemical Plant Security?, December 27, 2005

- NJ Issues Chem Plant Safety Regs; Including Safer Technologies, December 1, 2005

- WMD Found! Look Over Your Shoulder, May 9, 2005

- "We can't protect ourselves if we are not part of the plan", February 20, 2005

- NY Chem Company Decides Terrorism Threat Is Over, February 6, 2005

- Department of Homeland Security: Buddy Can You Spare a Dime?, September 27, 2004

- Chris Cox & Tim Russert: Educate Yourselves!, July 17, 2004

- If Safety Was Voluntary, Only Volunteers Would Be Safe, April 8, 2004

- Chemical Industry Steps Up To the Plate...And Strikes Out, June 26, 2003

- Weapons of Mass Destruction Found -- In Our Backyards, November 17, 2003

- The War for Chemical Plant Safety, May 4, 2003