Happy Sunshine Week!

Huh?

Yes, this is the first national

Sunshine Week, an event sponsored by more than 50 news outlets, journalism groups, universities and the American Library Association to focus on the issues that surround the freedom of the press and government openness.

And it has never been needed more than it is now. There is a great debate raging in this country, mostly behind the scenes, that will impact the safety of this nation's first responders, as well as citizens living in the vicinity of industrial facilities that use significant amounts of chemicals. The debate is over the right of workers and citizens to know what chemicals they may be exposed to. It's a battle that was largely fought and won years ago, but is being refought again under the specter of terrorist threats.

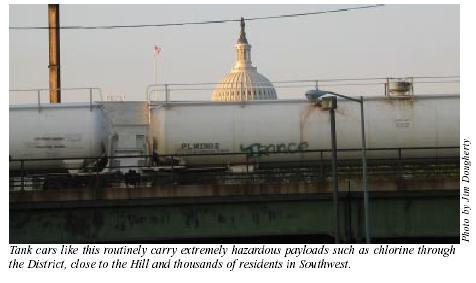

Last week I wrote an article entitled "

First Kill The Responders" about a Homeland Security Department proposal to remove the hazard identification placards from railroad chemical tank cars in order to protect the country from train-targeting terrorists. First responders who have a need to know what they're confronting are not amused.

Meanwhile, an rail accident last week in Salt Lake City shows that while the battle over the right-to-know, it's apparent that we've still got a long way to go before

right to know, actually becomes

the ability to know:

A railroad tank car that leaked toxic fumes, forcing thousands of people from their homes, was not designed to hold the mixture of highly corrosive acids with which it had been filled, the car's owner said Monday.

Some 6,000 people were allowed to return home and highways were reopened Monday after crews pumped the hazardous brew of waste out of the tank car.

Tests showed the tank car had been filled with a mixture of acetic, hydrofluoric, phosphoric and sulfuric acids, which easily corroded the car's lining, said Louie Cononelos, a spokesman for Kennecott Utah Copper of Magna, Utah.

Cononelos said the car was supposed to be used only for hauling sulfuric acid.

The copper mining company owned the car, but Philip Services, a hazardous waste handler, had leased it, and was using it to haul waste belonging to its customers. Philip Services spokesman Paul Schultz said the load complied with federal Transportation Department guidelines on the shipment of hazardous materials.

South Salt Lake Fire Chief Steve Foote said the incident could lead to a criminal investigation.

Officials said 6,000 gallons of liquid was pumped out of the car and it was believed about 6,500 gallons more had leaked and soaked into the ground. Contaminated soil will have to be neutralized with lime and removed, they said.

And the plot thickens. On one hand, this tanker had one of the placards that the Department of Homeland Security is proposing should be removed. On the other hand, it was wrong. Even thought the tanker was carrying a variety of highly dangerous acids, the placard showed only sulfuric acid. And although the shipping manifests were recovered,

they were so confusing that it took two days to figure out what was in the tanker.

The spill at the Union Pacific rail yard in South Salt Lake sent an orange cloud of potentially lethal gases over a several-block area. Several roads and highways, including a stretch of Interstate 15, were shut down for almost a day.

Watching a crew member poke a pen through the tanker's solid steel wall, South Salt Lake Fire Chief Steve Foote had no clue exactly what he was dealing with.

"It wasn't until two days after the incident that we had the state lab bring the results," Foote said Wednesday. "There was a lot of misinformation."

At issue is the tanker's Uniform Hazardous Waste Manifest, a federal government form as bureaucratic as it sounds - full of confusing numbers and dry legalese.

It's supposed to provide a complete paper trail of a hazardous shipment, and it should be a source for police, firefighters and any others who need accurate and accessible information to safely respond to toxic spills.

But critics say police and firefighters, who respond to a wide range of emergencies, can't be expected to make sense of the arcane jargon on the form.

"It's a whole plethora of numbers, codes and abbreviations, and that makes it difficult to follow through on what these things mean," Foote said. The manifest for last weekend's tank car was so puzzling that he assigned an entire team to make sense of it.

The

Association of American Railroads, which likes to boast of the safety of chemical transport by rail, thinks this is all much ado about almost nothing:

Rail is the safest method of shipping hazardous materials. Railroads have an outstanding track record in safely delivering hazardous materials – 99.9998 percent of hazardous materials carloads arrive at their destination without a release caused by a train accident. Hazmat accident rates have declined 87 percent sine 1980 and 34 percent since 1990.

That railcar in Salt Lake City (as well as January's South Carolina

chlorine train accident that killed nine), must have been among the .0002 percent. And this statistic kind of misses the point. We're concerned here about low probability, high impact accidents. 99.9998 percent sounds good, unless that .0002 percent is really bad stuff that get's released in a highly populated area.

All of these accidents, as well as the continuing debate over chemical plant safety, heighten the stakes of the Right-to-Know debate. Is there too much easy information available for our security? Is there too little? Is what's available too hard to understand or is it too easy to understand?

Last month we even saw chemical manufacturers and the government of the chemical-laden state of New Jersey actually

keeping the unions that represent the workers in the chemical plants in the dark while developing chemical plant security plan.

Meanwhile, the

American Railroad Association, along with the Departments of Homeland Security and Justice, are arguing that Washington D.C.'s recently passed ban on hazardous rail transport through the city will actually “increase exposure to possible terrorist action.” Their reasoning?

The Department of Justice and Department of Homeland Security said the DC law would “result in a dramatic increase in the total miles over which such materials travel and the total time the materials are in transit,” and "increase their exposure to possible terrorist action."

Well, yeah, but if re-routing the material through less densely populated areas -- even if it covers more distance -- means that a terrorist attack would kill far fewer people, wouldn't that actually

reduce the threat of terrorism? Or am I missing something?

The issue seems to transcend normal political divisions. In solidly Republican Utah, for example,

people are particularly concerned about their right to know:

In Utah, the public's right to know what is being shipped is an issue not only in the wake of the March 6 spill, but in the debate over plans to ship high-level nuclear waste to the Skull Valley Goshute reservation 50 miles west of Salt Lake City.

Chip Ward, co-founder of the Healthy Environment Alliance of Utah, said the potential transport of nuclear waste through the state underscores the importance of accessible information.

The risks, he said, "approach a whole different scale when you talk about transporting nuclear waste."

But there are signs that common sense seems to be breaking out -- at least among the front-line responders:

[South Salt Lake Fire Chief Steve]Foote said the likelihood of an accident is greater than a terrorist attack. Removing the placards is exchanging one risk for another, he said.

"We're starting to have more and more of these [accidents], but as far as I know, none of them has actually been sabotaged," he said.

Since 1973, 47 people have died in the United States as the result of tank cars either failing or derailing, Federal Railroad Administration statistics show. The most recent accident, on Jan. 6, killed nine people in Graniteville, S.C., when a derailed tank car spewed chlorine.

Between 1990 and 2004, there were 504 documented releases from 881 tank cars hauling hazardous materials,prompting the evacuation of a total of 144,497 people.

Warren Flatau, spokesman for the Federal Railroad Administration, did not believe any of the accidents were the result of sabotage.

And if we really need something to fear, let's not forget the recent

National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) report that warned that

as many as half of the 60,000 tank cars in service in the United States do not meet current industry standards, making them more susceptible to rupture. The media is slowly catching on to the threat. Orlando Sentinel columnist Myriam Marquez recently published widely syndicated

op-ed strongly defending the public's right to know"

The public’s “right to know” stands as the centerpiece of any democracy. Without informed citizens, there can be no real government accountability. Access to what government is doing is everybody’s business.

Since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, our rights have been dismissed as a threat to national security, and many Americans accept the blackout as necessary to secure liberty. That’s the tough sell democracy faces under today’s climate of fear from terrorism

***

Congress was duped when it gave companies the right to hide from the public information about the chemicals they store or information about other "critical infrastructure." That’s part of the law creating the Homeland Security Department.

If people living in the vicinity of, say, a chemical plant don’t know what’s being stored, how much of it, and what type of safety plans the company has in place, are those folks any safer than if they had that information and knew what they might face from an accident or even an attack on the plant?

It used to be that the Environmental Protection Agency’s Web site contained environmental reports filed by chemical plants so that the public could know what types of potentially poisonous materials were near their homes, businesses or schools. The EPA yanked those from its site post 9/11.

Accidents are more likely than terrorist attacks on such plants. Now people are more vulnerable, not less, because they haven’t a clue what risks they face. Until it’s too late.

The situation is getting so ridiculous that

even conservatives are getting upset:

Last year a trade publication called Mine Safety and Health News asked the U.S. Labor Department for biographical information about a new deputy secretary it wanted to profile. The department refused.

The information, it said, would invade his privacy.

Privacy and national security are big reasons for the clampdown on public information from Washington. From Vice President Dick Cheney's energy task force to information about the safety of dams in the Carolinas, many federal records have become off-limits. But critics say secrecy has become part of the culture.

"In the last 30 years, we've never had an environment that's been as hostile to openness as we have now," says Pete Weitzel, coordinator of the Coalition of Journalists for Open Government.

***

In Congress, many Republicans and Democrats are trying to open the doors of government wider.

"Conservatives are realizing that transparency is big government's biggest enemy," Mark Tapscott, director of the conservative Heritage Foundation Media and Public Policy Center, told a Newhouse News reporter last month. "Some conservatives have had a tendency to mistake an emphasis on the importance of transparency with long-haired college professors."

Let's all have a happy Sunshine Week. It may be your last.